Close Considerations

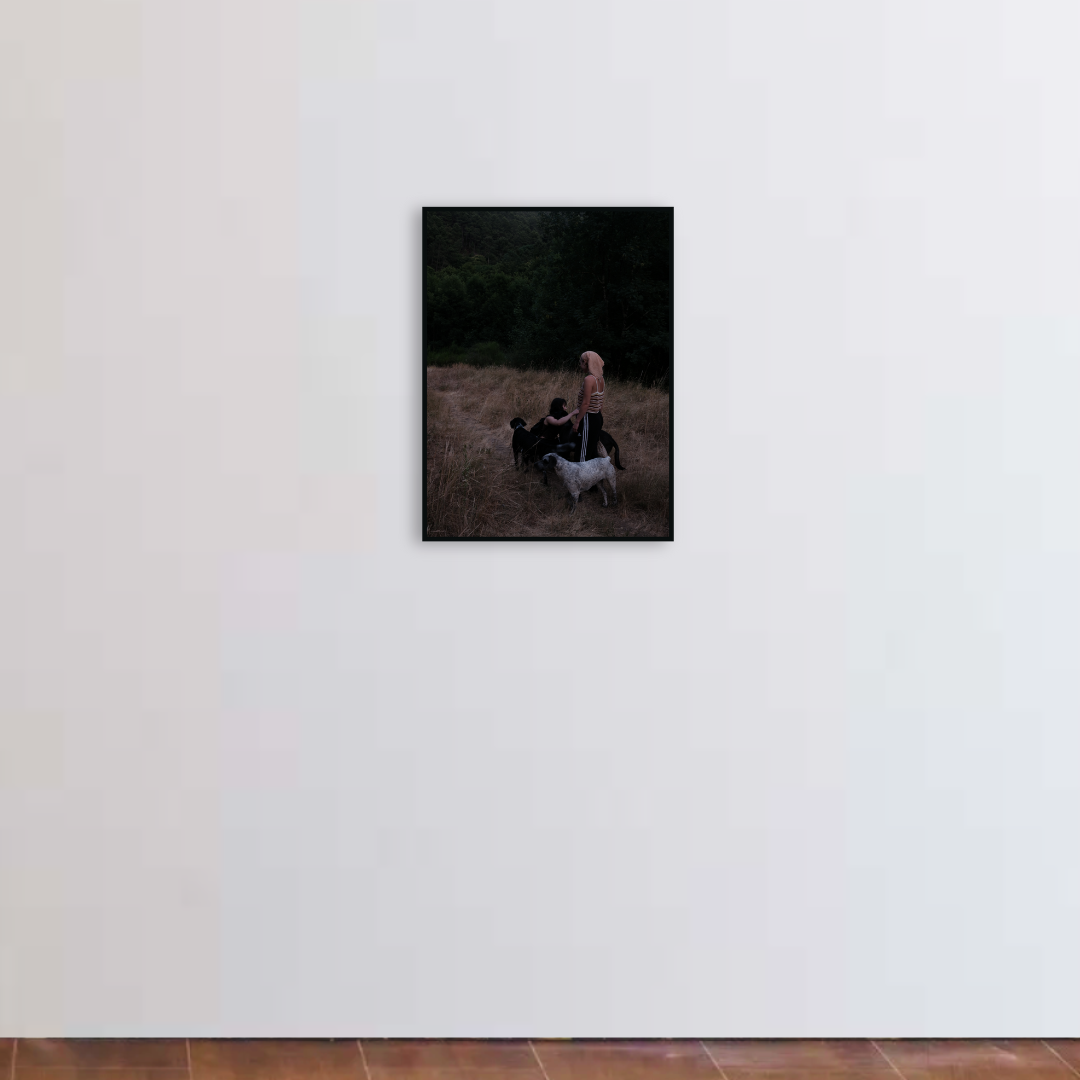

Telepathic connection in group dynamic: Within this tranquil yet eerie picture, the human figures are made more vulnerable by their proximity to the dogs. Their huddled posture suggests a potential threat. The human figure standing upright, facing outward like the two dogs at the periphery, hints at a telepathic connection, suggesting a psychological merger.

Psychological intrigue in contrasting elements: The softness of most elements, including the light, textures, grass, and dark background, combined with the slow movement of the figures, suggests a psychological state of lassitude indicative of post-exertion rest. However, vigilance towards the foreboding landscape persists as all-consuming darkness looms, which is complicated by contrasting with the curved light foreground, which offers the illusion of the ground rising upwards like the sun imbuing the figures with a regality.

Dispersing gaze in spiral configuration: The apparently isolated intimate group of figures, directs our attention. The seated figure, removing lice from the dog, points with her hand, leading our gaze towards the standing figure and ultimately to her distant gaze beyond the frame. This gaze, echoing the direction of the dogs', disperses our focus towards the dogs' heads and their orientation. Our attention thus spirals from the seated figure to the standing human and then scatters through the dogs and then away, in a vertiginous configuration.

Figures' orientation in proximity of threat: The contrast between the detailed foreground and the simpler background, coupled with the stark bifurcation, creates a perceptual distance. The minimal detail of the background slightly flattens it, making it challenging to assess actual distance through depth. However, the figures' orientation suggests that the threatening background is within close proximity, augmented by the dogs' alert posture. The standing figure's slightly bowed head, seemingly gazing towards something just outside the frame, indicates the proximity of the object of their alertness approaching from there.

Progression of time through light and space: The picture’s meaning unfolds within the image itself, both in time through light and space, progressing from the undifferentiated blurry background of the past to the stark, light-revealed climax of the present. This progression is emphasised by the intensification of light, colour saturation, and textural clarity (Nochlin, 1985, p.32),1 leading the viewer from darkness and blur to brightness and clarity, ultimately then towards the viewer.

Off-balance axis: The bifurcation between the illuminated foreground and the lush, dark background follows a diagonal axis extending from the bottom right to the middle left point outside the frame, aligning with the standing human figure's eye level. This axis is accentuated by a walking path of flattened grass, which appears to vanishes into obscurity by the grass on the left and the figures on the right, creating a line that guides the viewer's eye along the same diagonal towards the top left. This off-balance axis lends an unstable quality to the figures as if they are on the falling side of a slope.

Discontinuities, asymmetries, and open frames: Lerma's breaks the focus by using discontinuities, asymmetries, and open frames enriching this scene by disrupting its visual harmony and preventing rigidity. John Slyce (2000) notes, "The frame sets limits while offering a tangible means of escape."2 Lerma achieves this through cropped sections, leading lines extending beyond the frame, figures interacting with off-frame elements, and awkward props.

Notes:

1 Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

2 Slyce, John. On Time, Performative Realism: The Photographs of Sarah Jones, Museum Folkwang, 2000.

Process

Pre-emptive intuitional composing: Lerma's process involves anticipating and capturing spontaneous configurations among her friends in various spaces, employing intuitive pre-emption to preserve the moment's energy and mystique. She utilises specific camera settings, such as a wide aperture and slow shutter speed, to capture details in dimly lit spaces, contributing to the mood and emotional depth. She strategically positions herself or awaits the ideal light or for her subjects to assume particular poses or interactions, balancing spontaneity with a clear intention regarding the desired capture, resulting in organic yet meticulously crafted compositions.

Unprivileged view: Lerma's compositions align with Tillmans' notion of the "unprivileged view" (Godfrey, 2017),1where the artist's presence minimally influences the scene. Subjects often remain oblivious to Lerma, creating an atmosphere that "provokes a feeling of not mattering rather than command" (Ibid.),2 enabling the viewer to engage with the scene without undue artist interference.

Embedded ethnography: Lerma assumes the role of a "documentary observer," employing a systematic process of observation to allow the landscape to reveal itself without imposition, as articulated by hooks (1997).3 From within the communitas, Lerma offers a literal perspective aligned with Turner's concept of “heroic time,” rendering her an effective anthropologist of her own culture (Turner, 1985).4 Her ethos mirrors the communitas' values, characterised by a spontaneous and immediate approach to relationships. Subjects within the communitas retain the autonomy to approve or withdraw consent for the use of their photographs.

Process as political action: Rancière's (1999)5 framework on the “aesthetics of politics” posits that art transforms into political activity by disrupting the established symbolic order through the exposure of previously invisible elements. Lerma's practice, while intertwined with her political life, differs from photojournalism, which presents events as mere records or spectacles. Conversely, Lerma captures "the image of the photographic rhetoric that is purported to capture the event" (Guerra, 2006),6 offering a comprehensive understanding of the group's actions and underlying processes.

Disconnected instants and implicit intertextuality: Lerma's works, presented in artist books with variable image sequences, allow each work to be viewed within diverse contexts. This lack of a fixed sequence creates a dynamic constellation of "disconnected instants" (Berger & Bohr, 1982),7 where juxtaposition generates echoes, contrasts, and recurrences, forming "implicit intertextuality" (Ricœur, 1984).8 While the book format provides a meta-continuation, Lerma's practice of altering the sequence ensures each picture's autonomy, reinforcing its individual sovereignty.

Iterative composing and tautological reinforcement: Lerma's iterative compositional process generates multiple variants to elucidate the core structure and select the most impactful representation. This tautological approach reinforces the compositional elements' conjunction and interrelationships, as Allison Smith (1998)9 asserts. Despite facial anonymity, Lerma offers hints about her subjects' identities through body language and poses across different tautological contexts, facilitating viewer interpretation of actions and interactions, and engendering a viewer-subject relationship.

Notes:

1 Godfrey, Mark. Worldview. In Wolfgang Tillmans 2017, edited by Chris Dercon, Helen Sainsbury, and Wolfgang Tillmans, Tate, 2017, pp.14-76.

2 Ibid.

3 hooks, bell. “Between Us: Traces of Love—Dickinson, Horn, Hooks.” In Earths Grow Thick, Wexner Center for the Arts, 1997.

4 Turner, Victor. On the Edge of the Bush. 1985.

5 Rancière, Jacques. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

6 Guerra, Carles. Notre Histoire, Catalogue of the Exhibition. Paris: Palais de Tokyo, 2006.

7 Berger, John, and Jean Bohr. Another Way of Telling: A Possible Theory of Photography. Bloomsbury, 1982.

8 Ricœur, Paul. Time and Narrative. Translated by Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer, University of Chicago Press, 1984.

9 Smith, Allison. Agnes Varda. Manchester University Press, 1998.

References

Hitchcockian Vertigo: The clifftop setting evokes vertigo and danger, indicating the precariousness of the situation. Lerma has cited Hitchcock's cinematic portrayal of vertigo as a strong inspiration. While the spiral in other works makes this more explicit, the dizzying disorientation can result from looking down from the edge, the sense of disorientation and potential loss of control in the face of nature's power, reflecting the psychological disorientation (Hurley, 1993).1 The individuals depicted seem to be in a state of perpetual vertigo that renders them indifferent to the physical elements.

Vinca Petersen: Lea Lerma's reference to Vinca Petersen, the artist and former nomadic squat dweller, highlights their shared experiences. While Petersen's group embraced rave and party culture, Lerma's resonance aligns more closely with Petersen's depictions of interpersonal connection and natural landscapes, capturing moments of ecopsychological euphoria. (Image: work from Future Fantasy series by Vinca Petersen, Collage and art direction Ben Ditto. Published by Ditto © 2017)

Goya’s progression of time through light and space: Goya's Third of May unfolds temporally and spatially within the pictorial field. The narrative progresses from an undifferentiated background, describing the 'before,' to a climactic, light-revealed execution scene, representing the 'now,' and concludes with fallen figures at the pictorial boundary, signifying the 'afterwards.' This temporal progression is boosted by light intensity, colour saturation, and materiality, as noted by Nochlin (1985).2

Surrealism: Similar to the problematic light effects in the works of Delvaux, De Chirico, Ernst, Dali, Tanguy, and Miró, Lerma's work features an unknowable light source that bathes the figures in unnatural scenes that appear staged or digitally manipulated. The forest setting, devoid of any discernible light source, is illuminated by both hard and soft light, casting ominously thick black shadows from architectural elements. This juxtaposition of light and darkness creates a menacing atmosphere.

Andrei Tarkovsky's Landscapes: Tarkovsky's portrayal of humanity in a state of loss within natural landscapes is recalled in Lerma's work, which, through her community's actions, evokes a similar sense of being enveloped by expansive and immersive scenes. Lerma's compositional structures echo Tarkovsky's landscape aesthetics. (Image: Andrei Tarkovsky, Stalker, 1979)

Caspar David Friedrich’s romanticism: Friedrich Schleiermacher, a contemporary of Caspar Friedrich (whom Lerma cites as an influence), redefined religion as an internal, instinctual experience, departing from doctrinal interpretations (Butin, 2014).3 While Friedrich' s and Lerma's works depict nature, this particular picture of Lerma’s subverts the traditional hope of transcendental possibilities. Instead, it presents a state of oblivion, akin to imminent psychological death and complete disillusionment, yet replete with potential dopamine and serotonin effects. (Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, 1819–1820)

Clement Cogitore's Work: Cogitore, another reference point of Lerma’s, explores themes of irrationality, archaic schemas, primitivism, sacred survival, magic's infiltration into a world losing faith in transcendence, and apocalyptic figures. Ancient forms are recontextualised through contemporary image perception, where technology and the internet have replaced magic, yet the unconscious remains in pursuit of belief (Vergne, 2018).4

Fairytales: Lerma's visual narrative draws from historic fairytales, featuring ordinary protagonists immersed in fantastical realms (Swann Jones, 2013).5 Like Red Riding Hood and Snow White, Lerma's protagonists are young adults transitioning into adulthood, venturing into uncharted territories (Lüthi, 1976)6 and defining themselves (Flores, 1996).7Fantastical elements in Lerma's work facilitate suspension of disbelief (Vasudeven, 2017).8 The depicted moments remain authentic, subtly altered by Lerma's presence, perspective, and technique, creating a captivating dissonance in the fantastical scenes grounded in reality.

Sarah Jones and Dutch-Flemish Painting: Lerma's works, including this one, often exhibit structural configurations similar to Jones's pictures and Dutch-Flemish painting. Figures appear deeply engrossed, while settings pulsate with subtle significance (Higgie, 2000).9 A system of micro-signs forms a psychological narrative, with hints found in hand and foot positioning (Troncy, 2000).10 Lerma's brilliance lies in the silent interplay of places, objects, and people, which convey the intensity of a Greek drama (Higgie, 2000).11

Rembrandt, Caravaggio and Vermeer: Lerma's work resonates more with Rembrandt than Caravaggio or Vermeer, all of whom she mentions in discussing her practice. Her figures though caught in chiaroscuro-like moments and in quiet poses of Vermeer, exhibit Rembrandt’s quality of calm yet bold receptivity and a sense of awe towards the potential for transcendence within the ordinary. The evanescent light on the figures, sometimes subtle and other times radiant, imbues them with a mystical connection.

Nan Goldin: Lerma's work is influenced by Nan Goldin's exploration of intimate relationships, capturing moments of isolation, self-revelation, and adoration (Sussman, 1996).12 However, Lerma's approach differs from Goldin's photojournalistic snapshots, as Lerma's work is meticulously composed through pre-emption and tautology, resulting in a unique, rigorous, and more metaphysical visual language.

Notes:

1 Hurley, Neil P. Soul in Suspense: Hitchcock’s Fright and Delight. Scarecrow Press, 1993.

2 Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

3 Butin, Hubertus. Gerhard Richter’s Editions and The Discourses of Images. In Gerhard Richter Editions 1965–2013, edited by Hubertus Butin, Stefan Gronert, and Thomas Olbricht. Hanje Cantz, 2014.

4 Vergne, Jean-Charles, and Clement Cogitore. Le Prix Marcel Duchamp. SilvaneEditoriale, 2018.

5 Swann Jones, Steven. The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of the Imagination. 1995.

6 Lüthi, Max. Once Upon a Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. F. Ungar Pub. Co,1976.

7 Flores, Nona C. Animals in the Middle Ages: The Book of Essays. 1996.

8 Vasudeven, Alexander. “Reassembling the City: Makeshift Urbanisms and the Politics of Squatting in Berlin.” The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting. Verso, 2017.

9 Higgie, Jennifer. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

10 Troncy, Eric. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

11 Ibid (9)

12 Sussman, Elisabeth. Nan Goldin: I’ll be Your Mirror. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996.