Close Considerations

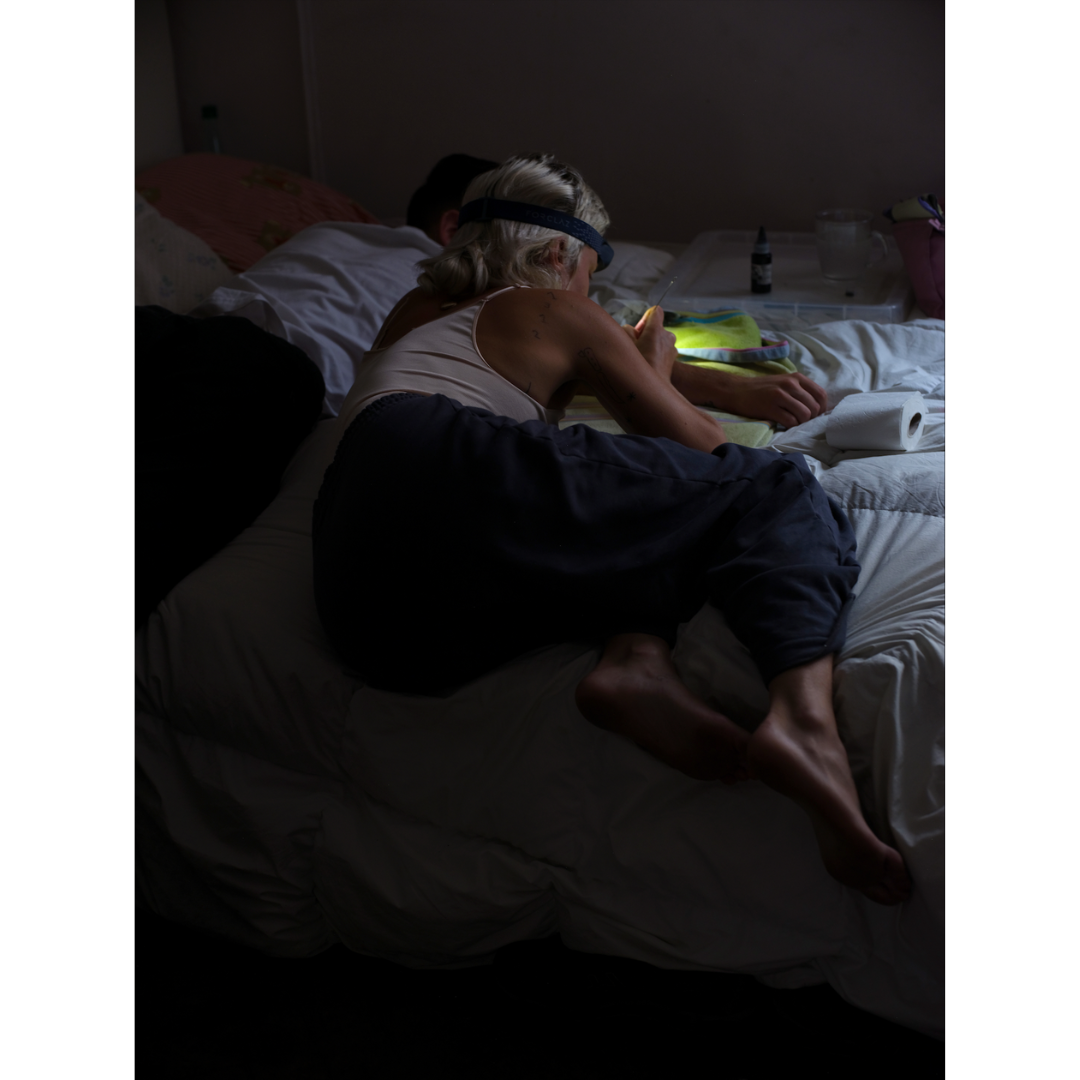

Fabric, light, and intimacy: The fabrics employed in this work establish a romantic setting, draped around and beneath the figures on the bed. The intimate, translucent light casts a sensual atmosphere as one figure, rolled over in utter submission, yields to the tattooer's invasive action of inserting the needle into the figure's skin, further emphasising the intimacy.

Progress of time through light and space: Lerma's work presents a progressive unfolding of meaning, transitioning from a blurred background to a light-revealed climax. This transformation is marked by intensified light, colour saturation, and materiality (Nochlin, 1985, p.32),1 leading the viewer from darkness to clarity. Central to this transformation is the fluorescent light emanating from the tattoo, lending the scene a Rembrandt-like metaphysical atmosphere, as if guided by divinity itself, through the overall light's "ebbing and flowing in softly throbbing waves," deepening the temporal and spatial journey within the work (Scott & Hillyard, 2019;2 Hertel, 1996).3

Converging and diverging axes: The main index is structured by three converging axes formed by the figures' poses, guiding the viewer's eye towards the merged heads to the hand, the focal point radiating light outwards. These axes, originating outside the frame, converge and then diverge, leading the viewer's gaze back out. Despite the strong index, Lerma introduces movement and complexity, allowing the viewer's eye to wander freely.

Protecting anonymity: Lerma ensures the obfuscation of faces in compositions depicting subjects engaged in political activities. This deliberate anonymity mitigates the potential for social ostracism from the urban middle classes. The ambiguous identity thus engendered invites a broader spectrum of interpretive inquiry and imaginative engagement (hooks, 1997).4

Concealment and nocturnal creativity: Subdued lighting, a common feature in Lerma's compositions, reflects her personal experience of occupying and residing in an abandoned building, which necessitated concealment from external observers to avoid detection. The nocturnal moments provided opportunities for introspection and creative pursuits, unburdened by daily demands and distractions.

Notes:

1 Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

2 Scott, Jennifer, and Hillyard, Helen. Rembrandt’s Light. London: Philip Wilson, 2019.

3 Hertel, Christiane. Vermeer: Reception and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

4 hooks, bell. “Between Us: Traces of Love—Dickinson, Horn, Hooks.” In Earths Grow Thick, Wexner Center for the Arts, 1997.

Process

Pre-emptive intuitional composing: Lerma's process involves anticipating and capturing spontaneous configurations among her friends in various spaces, employing intuitive pre-emption to preserve the moment's energy and mystique. She utilises specific camera settings, such as a wide aperture and slow shutter speed, to capture details in dimly lit spaces, contributing to the mood and emotional depth. She strategically positions herself or awaits the ideal light or for her subjects to assume particular poses or interactions, balancing spontaneity with a clear intention regarding the desired capture, resulting in organic yet meticulously crafted compositions.

Unprivileged view: Lerma's compositions align with Tillmans' notion of the "unprivileged view" (Godfrey, 2017),1 where the artist's presence minimally influences the scene. Subjects often remain oblivious to Lerma, creating an atmosphere that "provokes a feeling of not mattering rather than command" (ibid),2 enabling the viewer to engage with the scene without undue artist interference.

Embedded ethnography: Lerma assumes the role of a "documentary observer," employing a systematic process of observation to allow the landscape to reveal itself without imposition, as articulated by bell hooks (1997).3 From within the communitas, Lerma offers a literal perspective aligned with Turner's concept of “heroic time,” rendering her an effective anthropologist of her own culture (Turner, 1985).4 Her ethos mirrors the communitas' values, characterised by a spontaneous and immediate approach to relationships. Subjects within the communitas retain the autonomy to approve or withdraw consent for the use of their photographs.

Process as political action: Jacque Rancière's (1999)5 framework on the “aesthetics of politics” posits that art transforms into political activity by disrupting the established symbolic order through the exposure of previously invisible elements. Lerma's practice, while intertwined with her political life, differs from photojournalism, which presents events as mere records or spectacles. Conversely, Lerma captures "the image of the photographic rhetoric that is purported to capture the event" (Guerra, 2006),6 offering a comprehensive understanding of the group's actions and underlying processes.

Discontinuities, asymmetries, and open frames: Lerma's breaks the focus by using discontinuities, asymmetries, and open frames enriching this scene by disrupting its visual harmony and preventing rigidity. John Slyce (2000)7 notes, "The frame sets limits while offering a tangible means of escape." Lerma achieves this through cropped sections, leading lines extending beyond the frame, figures interacting with off-frame elements, and awkward props,

Disconnected instants and implicit intertextuality: Lerma's works, presented in artist books with variable image sequences, allow each work to be viewed within diverse contexts. This lack of a fixed sequence creates a dynamic constellation of "disconnected instants" (Berger & Bohr, 1982),8 where juxtaposition generates echoes, contrasts, and recurrences, forming an "implicit intertextuality" (Ricœur, 1981).9 While the book format provides a meta-continuation, Lerma's practice of altering the sequence ensures each picture's autonomy, stressing its individual sovereignty.

Iterative composing and tautological reinforcement: Lerma's iterative compositional process generates multiple variants to elucidate the core structure and select the most impactful representation. This tautological approach reinforces the compositional elements' conjunction and interrelationships, as Allison Smith (1998)10asserts. Despite facial anonymity, Lerma offers hints about her subjects' identities through body language and poses across different tautological contexts, facilitating viewer interpretation of actions and interactions, and engendering a viewer-subject relationship.

Notes:

1 Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

2 Scott, Jennifer, and Hillyard, Helen. Rembrandt’s Light. London: Philip Wilson, 2019.

3 Hertel, Christiane. Vermeer: Reception and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

4 hooks, bell. “Between Us: Traces of Love—Dickinson, Horn, Hooks.” In Earths Grow Thick, Wexner Center for the Arts, 1997.

5 Rancière, Jacques. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

6 Guerra, Carles. Notre Histoire, Catalogue of the Exhibition. Paris: Palais de Tokyo, 2006.

7 Slyce, John. On Time, Performative Realism: The Photographs of Sarah Jones, Museum Folkwang, 2000.

8 Berger, John, and Jean Bohr. Another Way of Telling: A Possible Theory of Photography. Bloomsbury, 1982.

9 Ricœur, Paul. Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences: Essays on Language, Action and Interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

10 Smith, Allison. Agnes Varda. Manchester University Press, 1998.

References

Vinca Petersen: Lea Lerma's reference to Vinca Petersen, the artist and former nomadic squat dweller, highlights their shared experiences. While Petersen's group embraced rave and party culture, Lerma's resonance aligns more closely with Petersen's depictions of interpersonal connection and natural landscapes, capturing moments of ecopsychological euphoria. (Image: A journey to Ukraine with volunteers and two 7.5 ton lorries full of aid, which had been collected through visitors to the Still Looking exhibition, 2000. Source: vincapetersen.com © Vinca Petersen)

Goya’s progression of time through light and space: Goya's Third of May unfolds temporally and spatially within the pictorial field. The narrative progresses from an undifferentiated background, symbolising the 'before,' to a climactic, light-revealed execution scene, representing the 'now,' and concludes with fallen figures at the pictorial boundary, signifying the 'afterwards.' This temporal progression is emphasised by light intensity, colour saturation, and materiality, as noted by Nochlin (1985).1 (Image: The Third of May by Francisco Goya. Source: Wikipedia.org)

Sarah Jones and Dutch-Flemish Painting: Lerma's works, including this one, often exhibit structural configurations similar to Jones's pictures and Dutch-Flemish painting. Figures appear deeply engrossed, while settings pulsate with subtle significance (Higgie, 2000).2 A system of micro-signs forms a psychological narrative, with hints found in hand and foot positioning (Troncy, 2000).3 Lerma's brilliance lies in the silent interplay of places, objects, and people, which convey the intensity of a Greek drama (Higgie, 2000).2

Rembrandt, Caravaggio and Vermeer: Lerma's work resonates more with Rembrandt than Caravaggio or Vermeer, all of whom she mentions in discussing her practice. Her figures though caught in chiaroscuro-like moments and in quiet poses of Vermeer, exhibit Rembrandt’s quality of calm yet bold receptivity and a sense of awe towards the potential for transcendence within the ordinary. The evanescent light on the figures, sometimes subtle and other times radiant, imbues them with a mystical connection.

Nan Goldin: Lerma's work is influenced by Nan Goldin's exploration of intimate relationships, capturing moments of isolation, self-revelation, and adoration (Sussman, 1996).4 However, Lerma's approach differs from Goldin's photojournalistic snapshots, as Lerma's work is meticulously composed through pre-emption and tautology, resulting in a unique, rigorous, and more metaphysical visual language. (Image: Nan Goldin, Thora at my vanity, Brooklyn, 2021. Source: Gagosian.com © Nan Goldin)

Notes:

1 Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Penguin Books, 1985.

2 Higgie, Jennifer. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

3 Troncy, Eric. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

4 Sussman, Elisabeth. Nan Goldin: I’ll be Your Mirror. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996.