Lea Lerma

L’Envers de l’Endroit

PART 1

*16-minute study

Synopsis: In Part I/II of Sunend's survey of Lea Lerma's L’Envers de l’Endroit, we examine the lives of a communitas first formed during the COVID-19 lockdown. An abandoned building becomes the site of a micro-utopian experiment, which, following the lockdown, expands into the wilderness and evolves into a spiritual undertaking. Through chiaroscuro, layered spatial dynamics, and fairytale-like imagery, Lerma's lens-based practice investigates themes of autonomy, resilience, and collective belonging. Acts of trust and resistance—such as tattooing—unfold within an aesthetic framework that merges the fantastical and the real. Animals, light, and fragmented compositions emerge as semiotic markers, capturing the group's precarious yet fearless existence. This first part concludes by examining how Lerma’s non-hierarchical process transforms photography into a political act, reimagining freedom and presenting a vision of collective agency that transcends the limits of confinement.

Key references and methodology: This study employs a comprehensive interdisciplinary approach, combining cultural theory, art history, sociology, and ethnographic frameworks to explore Lea Lerma’s lens-based practice and its political underpinnings. Victor Turner’s theory of liminality provides a foundation for understanding the communitas as a group existing in a transitional, non-hierarchical space, while Roland Barthes’ "punctum" highlights the emotional disruptions embedded in Lerma’s imagery. Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s critique of kitschy middle-class sensibilities, the essay situates the group’s rejection of societal norms as a form of resistance. Comparisons to Renaissance works, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, illuminate the structural unity of Lerma’s compositions, while Nikki Sullivan’s exploration of tattoos as both self-expression and communal markers underscores the trust and intimacy inherent in the group’s rituals. The study also integrates Carles Guerra’s critique of photojournalistic rhetoric to differentiate Lerma’s embedded, unprivileged perspective from traditional modes of representation. Drawing from sociological studies on subcultures (Gelder, 2007), Turner’s exploration of Icelandic sagas, and Wolfgang Tillmans’ notions of free and fearless spaces, the essay positions Lerma’s work within a broader discourse on autonomy, freedom, and precarity. This layered methodology, supported by texts on temporality, symbolism, and micro-utopian practices, frames Lerma’s images as both aesthetic and political interventions, resisting linear narratives and engaging with her communitas’ experience in a fragmented, post-pandemic world.

Some works from L’Envers de l’Endroit at Copeland Gallery, London

Some works from L’Envers de l’Endroit at Copeland Gallery, London

I’ the commonwealth I would be contraries

Execute all things; for no kind of traffic

Would I admit; no name of magistrate;

Letters should not be known; riches, poverty

And use of service, none; contract, succession

Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none;

No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil;

No occupation; all men idle, all;

And women too, but innocent and pure…

- Act ii, scene 1, lines 141-49, The Tempest

When the second authoritarian lockdown was announced by French President Emmanuel Macron during COVID-19, Lea Lerma and her friends, already under psychosocial distress (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009),1 fled their homes and occupied an abandoned building. Their spatial reclamation turned into a micro-utopian experiment; a temporary social space designed to explore alternative social structures (Wood, 2007).2 The space provided them with the "opportunity to resituate their own struggles on the terrain of everyday life […] struggles over the right to autonomy and self-organisation" for which they brought "people, ideas, and resources together in new constellations of care, solidarity, and hopefulness" (Vasudevan, 2017).3

Séance tattoo à la lumière de la frontale

Séance tattoo à la lumière de la frontale

Lyon, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

The group's shared experience and social cohesion are reflected in this picture depicting a member being tattooed by another. Tattoos, as Nikki Sullivan (2001) suggests, serve a dual purpose: "both the external expression of an inner essence, and a (potential) source of knowledge, of mastery, and thus of freedom […] of the soul from the bounded space of the body […] a form of self-determination."4 The act of tattooing itself, particularly in this context where established protocols are disregarded, requires immense trust and submission between the tattooee and the tattoer, becoming a form of "communal membership […] where the tattoo is the membership badge [… and] presumes a lifelong" affiliation to the group (Richie & Buruma, 2000).5

Lea Lerma in practice

This is when Lea Lerma's current lens-based art practice evolved its political aspect, characterised by an unconventional methodology that, through extended and deliberate participant observation, she integrates herself into the political lives of her friends, becoming an embedded ethnographer within their social routines (Emerson, Fretz & Shaw, 2011).6 This grants her unparalleled access, enabling her to capture sincerely personal and vernacular moments rarely seen otherwise. Which is also the reason for the concealed faces in Lerma's pictures, to protect their pursuit of a lifestyle deemed deviant by kitschy middle-class sensibilities (Bourdieu, 2013).7

The consumer, supposedly sovereign, is nothing but the locus of a network of pseudo-choices […] we are guided through a pre-programmed set of options that reduce us to a mere linkage in a computerised system.

- Martin Jenkins, 20128

Following their growth in the temporarily occupied building, where they had to establish autonomous systems for water supply, access to food, as well as cultural events and social gatherings (Harvey, 2012),9 including film screenings and techno raves, the group's sense of cohesion solidified. Once the lockdown ended, they ventured further beyond into undisclosed locations in the French wilderness.

Sol, cueillettes dans les buissons de mûres

Sol, cueillettes dans les buissons de mûres

Lyon, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Communitas

Subcultures often form unique identities through communal spaces by fostering group cohesion and a sense of belonging (Gelder, 2007).10 Lerma's group, however, is not simply defined by a "refusal" of societal norms (ibid). Using Victor Turner's (1995) framework, they embody "liminal personae" in a "liminal space," positioned "betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention and ceremonial."11 This "communitas" lacks hierarchies and seeks a more organic, immediate mode of existence, contrasting with the "conformist pressures" of mainstream society (Gelder, 2007).12

Initiation at the Villa of Mysteries, Pompeii, a rite of passage expressing communitas. Pompejanischer Maler um 60 v. Chr., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Initiation at the Villa of Mysteries, Pompeii, a rite of passage expressing communitas. Pompejanischer Maler um 60 v. Chr., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Lerma’s communitas absconds annually to this liminal space in the French wilderness, unleashing their physical, mental, spiritual, and artistic selves (Coman, 2008).13 The period is filled with mythical potentialities, with the protagonists, whose ambiguous identities "invite another range of questioning and exercise of imagination" (hooks, 1997),14 imbuing them with a fantastical enigma.

I was always interested in the free, or at least non-branded, activities that functioned outside control and marketing. Those pockets of self-organisation—free partying, free sex, free leisure time—are on the retreat. A less commercial spirit of togetherness is worth defending against the market realities, which are the result of the implementations of an atomised, privatised model of society.

- Wolfgang Tillmans, 200815

The aesthetics of politics and the unprivileged view

Lerma's process is rooted in the political ethos of her communitas, subverting the traditional artist-subject dynamic. Her friends/subjects have full control over their portrayals and can withdraw their consent for their use at any time. Lerma's work, unlike photojournalism, captures a political process, reflecting "the image of the photographic rhetoric that is supposed to capture the event" (Guerra, 2006).16 By disrupting established orders and revealing the invisible her approach offers a holistic view of the group's activities, making her process itself a political act.

Sol, sieste sur le tapis de mousse

Grenoble, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

In her political process, Lerma employs the ‘unprivileged view,’ where her presence or absence makes little difference to the scene. Even when figures are slightly oriented toward her, they remain largely oblivious, creating a plain ordinariness that "provokes a feeling of not mattering rather than command" (Godfrey, 2017).17 Their temporally suspended, quiet movements enhance the scene's potency, as the figures don't confront or engage the viewer directly, yet the structuring of the composition still implicates the latter.

Norsemen Landing in Iceland, by Oscar Arnold Wergeland, 1877. Oscar Wergeland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Norsemen Landing in Iceland, by Oscar Arnold Wergeland, 1877. Oscar Wergeland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Lerma's art practice, as an aesthetic ethnographic narrative of her communitas, recalls the Icelandic Sagas examined by Victor Turner who questioned whether these oral traditions were always intended as works of art. A similar dilemma arises with Lerma's work. Unlike elite chieftains who recorded the sagas with their own political agendas, Lerma offers a more literal and detached perspective from within the communitas, in what Turner calls "Heroic Time" (Turner, 1985).18 Lerma's work, as a visual narrative, with its unprivileged view offers a vantage point that though aesthetically driven reflects the communitas’s experience aligning her closely with the cultural and social fabric she documents.

Spectrum/Dagger, 2014 by Wolfgang Tillmans

Spectrum/Dagger, 2014 by Wolfgang Tillmans

Free fearless uncontrolled and unsafe

In his interview about his work The Spectrum/Dagger, 2014, Wolfgang Tillmans talks about the ultimate social yearning of his in which people are “free, fearless, in an uncontrolled, but safe environment” (Tillmans, 2016).19 Although Lerma references Tillmans as an influence, Lerma’s communitas holds nothing back. Unlike the alternative kitsch found in urban ‘safe spaces,’ which prioritise health and safety while allowing certain people to be free, the space forged by Lerma's communitas is fundamentally unsafe, which is what makes it truly free. Her work counters the notion of ‘free and safe,’ showing us that a truly free life is indeed unsafe. Lerma's work offers a more compelling look at freedom than Tillmans's careful pictures.

Sol en chemin pour faire sa toilette à la rivière

Sol en chemin pour faire sa toilette à la rivière

Cevennes, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Wolf Time

Lea Lerma and her free and fearless communitas, having sought refuge in the uncontrolled and unsafe wilderness, inhabit a liminal space within the ‘wolf time,’ deriving from the 2003 horror/drama film title Time of the Wolf by Michael Haneke. The family in the film becomes severed from mainstream societal structures and must survive in the wild, where money is worthless and "danger lurks everywhere" (Brunette, 2010). 20 An intriguing parallel with Lerma’s communitas involves a wild child who abruptly emerges and forms a bond with the protagonist's family. The former also includes a young boy left in their care every year since he was nine years old. His immensely vulnerable presence introduces a thrilling dimension, his psychological state diverging from the young adults responsible for him.

Still from Time of the Wolf (2003) horror/drama movie by Michael Heneke

Still from Time of the Wolf (2003) horror/drama movie by Michael Heneke

Subliminal animal narrative

Within Lerma's pictures, specific animals function as semiotic markers, hinting at a concurrent narrative. Using Turner's (1985) theoretical framework on the inherent "semantic openness" of symbols, 21 we can analyse the symbolic presence of animals without falling into Kantian levels of irrationalism. Traditionally, animals in medieval art and literature served didactic purposes, conveying knowledge about existence or reflecting prevailing human values (Flores, 1996). 22 Lesley Kordecki (ibid.) builds upon this perspective, conceptualising animals as potent "textual agents" who function as "reflections, distortions, models, subversions, scapegoats" for the human animal.23

Sol et Mathilde, ascension en compagnie des chèvres

Drôme, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

The wolf, a prominent symbol in Lerma's work, underscores the conceptual application of ‘wolf time.’ Although absent from the images, its presence is felt through the decline in the goat population, revealing a latent concurrent narrative. Goats represent fertility and abundance, reflecting the communitas's aspiration for inner self-sufficiency (Hatto, 1973).24 Their precipitous decline due to being hunted by the wolves, historically negatively portrayed, associated with devastation and vengeance (Ibid), indicates Lerma and her communitas’s proximity to precarity.

Alternatively, the wolf could symbolise resilience and untamed vigour, mirroring the group's own spirit. Positioned between the symbols of wolf and goat, the communitas embodies both the tamed and untamed, the predator and prey. Therefore, the inclusion of dogs, closely related to wolves, introduces a centring element, representing domesticity, loyalty, and protection.

Lisa et Sol, contrôle des tics sur les chiennes

Cevennes, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

The scene of individuals on a quest, surrounded by goats, dogs and wolves, recalls biblical narratives. And Lerma conveys metaphysicality through subtle aesthetic configurations. This inkling can be described by considering Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, 1501-1519, which was the first time in Italian painting where the Virgin and St. Anna with the infant Christ were brought together. We see core structural elements of this picture in Lerma’s in two crucial ways: first is the landscape both immediate natural surrounding and the mountain(s) in the background. But more crucial is the unity of figures “established not only by gesture; they seem to merge into each other since they are inscribed into a pyramidal configuration” (Kris, 1988, p.19).25

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, c.1501-1519

Leonardo da Vinci

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Lea Lerma’s Fairytale Saga

Lerma's communitas are seen in the uncorrupted perfection of natural landscapes, in an ideal, classical stasis reminiscent of what Roland Barthes calls "mythological" (Bastide, 1991).26 Her visual narrative casts "ordinary people as protagonists" immersed in fantastical worlds (Swann Jones, 2013).27 The protagonists, young adults on the brink of irreversible adulthood, "break away from their accustomed environment" and venture into uncharted territories (Lüthi, 1976),28 "still in the process of defining themselves" (Flores, 1996).29 The moments depicted remain authentic, subtly altered by Lerma's perspective and positionality in relation to the subjects and the space, resulting in a captivating dissonance of fantastical scenes rooted in reality.

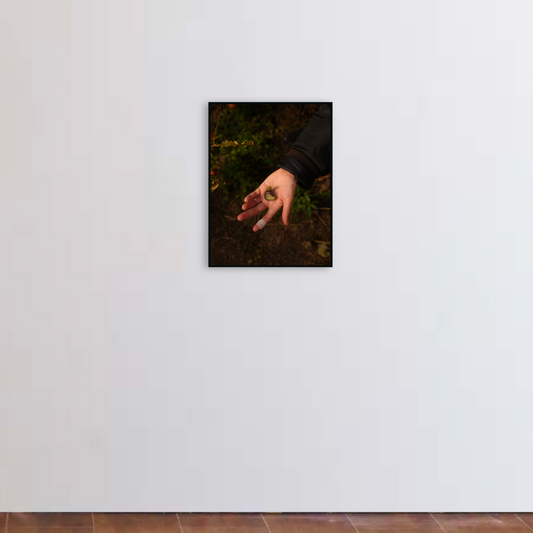

Sol me tendant un des fruits du potager

Sol me tendant un des fruits du potager

Drôme, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Quiet Gestures

Lerma's world, often free from modern life's cacophony, exudes a quiet power. Influenced by Sarah Jones and Dutch-Flemish painters, her work shares their "structural conventions of depiction and figuration," with figures appearing "intensely preoccupied" (Higgie, 2000).30 Unlike Jones and Dutch-Flemish painters, Lerma acts as a "documentary observer," allowing the scene to reveal itself without imposition (hooks, 1997).31

Sol et Lisa, cueillant des fleurs sur un bord de route

Sol et Lisa, cueillant des fleurs sur un bord de route

Cevennes, 2020

Inkjet print

30 x 26 cm

Edition 1/5

Signed, numbered, and dated

£300

Her subjects' slow, introspective gestures and interactions, mostly occurring in unstaged rural landscapes, make the images as much about the landscape as the individuals within it. This unique visual language reveals a psychological state through subtle "micro-signs," emphasising the silent interplay between places, objects, and people, expressing an intensity akin to Greek drama (Higgie, 2000).32

Woman Reading a Letter c. 1663, Johannes Vermeer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

End of PART 1

Notes Part 1

1 Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. “Perceived Social Isolation and Cognition.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 13, no. 10, 2009, pp. 447–454.

2 Wood, John. Design for Micro-Utopias: Making the Unthinkable Possible. 1st ed., Routledge, 2007.

3 Vasudeven, Alexander. “Reassembling the City: Makeshift Urbanisms and the Politics of Squatting in Berlin.” The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting. Verso, 2017.

4 Sullivan, Nikki. Tattooed Bodies: Subjectivity, Textuality, Ethics, and Pleasure. 2001.

5 Richie, Donald, and Ian Buruma. The Japanese Tattoo. 1st ed., Weatherhill, 1989, pp. 60–61.

6 Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press, 2011, pp. 21–39.

7 Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2013.

8 Jenkins, Martin. …and the Situation of the Spectacle. Society of the Spectacle, 2009.

9 Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. United Kingdom: Verso, 2012.

10 Gelder, Ken. Subcultures: Cultural Histories and Social Practice. New York: Routledge, 2007.

11 Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process. 1995.

12 Ibid (10).

13 Coman, Alina. Tehnici de comunicare: proceduri şi mecanisme psihosociale. C.H. Beck, 2008.

14 hooks, bell. “Between Us: Traces of Love—Dickinson, Horn, Hooks.” In Earths Grow Thick, Wexner Center for the Arts, 1997.

15 Bullock, Michael. “The Spectrum” [Interview with Gage of the Boone and Raúl de Nieves], Apartamento: An Everyday Life Interiors Magazine, no. 17, 2016, p. 127.

16 Guerra, Carles. Notre Histoire, Catalogue of the Exhibition. Paris: Palais de Tokyo, 2006.

17 Godfrey, Mark. Worldview. In Wolfgang Tillmans 2017, edited by Chris Dercon, Helen Sainsbury, and Wolfgang Tillmans, Tate, 2017, pp. 14–76.

18 Turner, Victor. On the Edge of the Bush. 1985.

19 Ibid (15).

20 Brunette, Peter. Michael Haneke. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

21 Ibid (18).

22 Flores, Nona C. Animals in the Middle Ages: The Book of Essays. 1996.

23 Kordecki, Lesley. "Making Animals Mean: Speciest Hermeneutics in the Physiologus of Theobaldus." In Nona C. Flores, ed., Animals in the Middle Ages: A Book of Essays, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1996, pp. 85–101.

24 Hatto, Arthur Thomas. The Nibelungenlied. Penguin Books, 1973.

25 Kris, Ernst. Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art. International Universities Press, Inc., 1988.

26 Bastide, Bernard. “‘Mythologies, me vous faites rêver’ ou mythes caches, mythes dévoilés dans l’œuvre d’Agnès Varda” in Etudes Cinématographiques: Agnès Varda. Paris: Lettres Modernes, 1991.

27 Swann Jones, Steven. The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of the Imagination. 1995.

28 Lüthi, Max. Once Upon a Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. F. Ungar Pub. Co, 1976.

29 Ibid (22).

30 Higgie, Jennifer. Sarah Jones. Le Consortium, 2000.

31 Ibid (14).

32 Ibid (30).

Some works from L’Envers de l’Endroit at Copeland Gallery, London

Some works from L’Envers de l’Endroit at Copeland Gallery, London